The Middle of The Mess -- Thoughts on Middle-Skills Health Care Careers

By Mario and Andrew

One of the themes we often hear from our partners is concern over America’s shrinking middle class. At the core of the issue is the well-recognized oddity: millions of job postings go unfilled even as millions of people remain unemployed or underemployed. The causes of this phenomenon are many and include skills gaps, opportunistic upskilling, significant workforce stakeholder fragmentation, and global forces of automation and outsourcing, among others. The systemic failure to create new, sustainable paths to the middle class is inflicting a serious cost on the competitiveness of American firms and on the productivity of American workers (and likely contributes to inputs that lead to Americans’ unhappiness) .

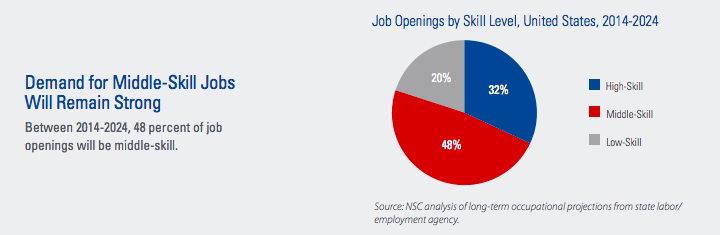

Middle-skills jobs, those that require education beyond a high school diploma but less than a four-year college degree, provide hope (though these jobs are not created equal). In many instances, this class of jobs pays a living wage, improve job security and satisfaction, and create career ladders capable of withstanding economic, political, and technological disruptions. Additionally, according to the National Skills Coalition, they are also projected to make up 48% of job openings through 2024.

The question we should ask ourselves, then, is: how can we create sustainable pipelines into middle-skills jobs with potential for advancement and/or are protected from global volatility?

NOT HEALTHY, CARING OR A SYSTEM - BUT LOTS OF UPSIDE?

By many measures—spending per capita, infant mortality rates, disease burden, hospital admission for preventable disease—the American health care system has massive room for improvement. According to Gallup, nearly 70% of all Americans believe health care is in a state of crisis.

Yet, with inexorable aging of the U.S. population it is clear that barring some fundamental paradigm shift (e.g. Medicare for all) or economic shock, health care jobs will slowly make up more and more of the labor force which creates an opportunity for improvement in outputs and outcomes and new pathways to the middle class. In fact, the health care sector is already moving in this direction as it recently surpassed retail and manufacturing to become the single largest source of jobs in the country. There are three core reasons for this trend:

The American population is growing older with a disproportionate share of the baby boomer generation moving into retirement and developing age-related illnesses that will demand more health care workers to service their needs,

Health care is multidimensionally publicly subsidized, making its jobs more stable than those in other areas (this also creates higher retention levels), and

Health care jobs tend to be more locally focused which makes them more resistant to the forces of globalization that have more directly impacted other sectors such as manufacturing, finance, information technology.

It should come as no surprise then, that the health care sector is also projected to produce a significant percentage of the new middle-skills jobs available for the foreseeable future. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, of the 30 fastest growing jobs— as measured by growth rate— through 2026, more than half are in health care with a majority being Tier I middle-skills opportunities including home health aides, personal care aides, physical and occupational therapy aides and medical receptionists. A significant number also include Tier II and Tier III positions such as community health workers, cardiovascular technologists, and imaging specialists.

THE MIDDLE-SKILLS HEALTH CARE MISALIGNMENT

Despite codified job growth, multiple studies have found that middle-skills jobs in health care are often difficult to fill as,

A significant number of potential employees lack the relevant credentials and certifications to qualify for many of these positions,

There is considerable employee turnover and difficulty with employee retention that inhibits the development of a stable cadre of peer instructors and mentors to sustain career growth, and

Many of these positions are filled by individuals from socioeconomically disadvantaged groups who struggle to maintain stable employment while dealing with challenges outside of work including access to stable housing, food, and good medical care (among others).

The typical paradigm of upskilling or reskilling that focuses on academic instruction followed by on-the-job training and placement is failing to systematically develop a robust middle-skills pipeline in health care. Of those who graduate from high school and continue on to some community college, a large percentage either fail to graduate, incur significant debt burdens, or both, and fail to develop the life skills and certifications required to compete for these health care positions. As a result, they also fail to break out of the cycle of poverty that fuels and sustains the underlying causes of the middle-skills supply-demand mismatch.

LOCAL PROOF POINTS

Programs such as West Dallas Pathways (in partnership with Baylor Scott White Health) and Parkland Hospital’s Rise to Success Program, are actively addressing key constraints to sustainable pathways. These programs are targeting high school students and other middle-skill eligible learners and piloting local approaches that aim to address the underlying challenges associated with housing, education, healthcare, and social stability that are often at the root of the worker supply side of the problem.

Through a cooperative model, often with a local community college or other certifying body, these programs put students in learner programs that offer employment followed by some period of payback in return for their sponsorship. In return, the students gain and develop credentials and certifications required to sustain a career in the health care industry.

While academic assistance is critical, the most successful of these programs also include additional evaluation and intervention efforts to mitigate the challenges associated with sustaining a job (particularly, for populations for the bottom 50% of income distribution in the United States). These interventions include social capital programming—e.g. relationship building, the creation of social cohorts that provide peer support—and economic support to subsidize personal needs, including childcare during the period of learning. By addressing the areas outside of the traditional academic training scope, these programs are fostering sustainability and longevity that will minimize employee turnover, improve applicant quality, and generate a greater return on the investment that it takes to build these partnerships.

EARLY REFLECTIONS

We are working on a number of projects todevelop pathways to prosperity via middle-skills jobs in health care, including a partnership with the College Board. There are critical lessons learned from our evolving work:

A narrow focus on creating middle-skills jobs in health care that either have strong potential for career advancement or are well insulated from external volatility makes strategic and tactical sense. Conversely, we should stop allocating resources and energy into creating pipelines to static middle-skills jobs in health care,

Interventions without a focus on technical and soft skills are doomed to fail,

There is a massive opportunity to reshape Americas’ perceptions of health care by focusing on the elevation of middle-skills health care careers focused on serving the elderly (America will increasingly be judged by how it treats the Baby Boomers), and

Industry certifications in health care don’t consistently serve as a lever to advancement. They are often not aligned to employer needs and inconsistent across geographies.

Advancing middle-skills careers in health care may represent the only opportunity to expand our middle class, prove we can serve our most vulnerable, and create models to advance middle-skills jobs we should be focused on in other sectors.